How to tell the difference between a genuine skeptic and a simple denialist

I suppose, as a general rule, the human animal is built to prefer knowing to not knowing, but I have been struck over the course of the past decade or so at how much worse our society has gotten at tolerating uncertainty. It’s as if having to say “I don’t know” triggers some kind of DNA-level existential crisis that the contemporary mind simply cannot abide.

I suppose, as a general rule, the human animal is built to prefer knowing to not knowing, but I have been struck over the course of the past decade or so at how much worse our society has gotten at tolerating uncertainty. It’s as if having to say “I don’t know” triggers some kind of DNA-level existential crisis that the contemporary mind simply cannot abide.

Perhaps this is to expected in a culture that’s more concerned with “faith” than knowledge, reason, education and science, but even our extremely religious history fails to explain the pathological need for certainty that has come to define too much of American life. Perhaps it’s due to fear. America is currently being slapped about by one hell of a perfect storm, after all:

- Change can be frightening, and we’re in the midst of perhaps the most dramatic wave of technological innovation in the history of civilization.

- Technical change drives social upheaval and stresses our coping mechanisms, which drives reactionary behavior. I wrote in more detail about the “fear gap” back in 2007 (and revisited some of the same issues in my December 2008 piece on the ethics of cloning a caveman) and I think those observations are growing more relevant by the day.

- Unfortunately, this explosion in the number of things that there are to know is being paralleled by a disheartening deprioritization of education, meaning that the gap between what the public understands and what it needs to understand in order to navigate this unsettling period of social evolution is growing by leaps and bounds.

Of course, nobody wants to be perceived as fearful or ignorant or overwhelmed or reactionary. Humans seek legitimacy for themselves and their beliefs, and in such a complex age it’s probably to be expected that we would see a rush to cloak fundamentalist impulses in the language of education and progress. Some are fine retreating into ever more regressive religious community, but more and more we’re seeing an appropriation of words like skepticism and debate, terms that attempt (often with some success) to situate pretenders in the midst of the scientific process.

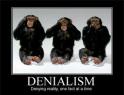

The truth is that a great many people who call themselves skeptics these days are nothing of the sort. “Skeptic” is a word with a long tradition in the context of good faith inquiry into the workings of our universe. While it’s impractical to ask that everyone familiarize themselves with that entire philosophical heritage, it is time we paused to consider the term in light of how it is used and abused in the controversies of the present moment and to assert a productive operational definition that helps us better distinguish who’s working to understand vs. who’s working to obfuscate. The more we allow the term to be bastardized and deployed in ways that are antithetical to its actual meaning, the more we undermine the scientific process itself. We must therefore insist on the appropriate use of “skeptic” and we have to be determined in calling out those who distort the word either out of ignorance or in the service of cynical political pursuits.

Skeptics vs. Deniers: A Workable, Citizen-in-the-Street Definition

So let’s take a stab. In essence, a genuine skeptic is someone who approaches claims to knowledge with a stance that insists on rigorous standards of evidence and demonstration.

When presented with a proposition, he or she asks “what evidence do we have to support this claim?” Evidence is scrutinized with a critical eye, and he or she thinks about things like possible alternate hypotheses. Is the condition or phenomenon real? If so, what else would it explain it? Is the evidence credible? Are those arguing for or against the hypothesis credible? Can findings be replicated? And so on.

Page 1 of 3 | Next page